(click to enlarge photos)

Twice I have heard from persons who were working downtown – one in the Exchange Building and the other in the Smith Tower – during the Second World War who described the strange bomber, trailing smoke, sputtering and flying much too low over the business district as it headed south in what test pilot Edmund T. Allen probably knew was a hopeless attempt to make it back to the Boeing Field it had left minutes earlier.

At 12:23 they heard – and many also saw – the still secret B-29 Superfortress first sever with arcing explosions the power lines north of Walker Street and then slam into one of the biggest structures in the industrial neighborhood, collapsing the northwest corner of the Frye meat packing building that was dedicated to the slaughter of pigs and the manufacture of, among other products, Frye’s big buckets of Wild Rose Lard. (The cans were famously illustrated with its namesake rose.)

Those who heard the surreal chorus of squealing pigs that followed the explosion described it as terrifying.

The death toll for that Feb. 18, 1943, included one fireman, twenty Frye employees and the ten from Boeing who stayed with the plane and two who did not. Most were engineers. Earlier when the bomber was close to colliding with Harborview Hospital, two engineers bailed out but there was not enough distance between the plane and First Hill for their parachutes to open. Eighty pigs did not make it to slaughter.

This famous press photo and scores more are included in Dan Raley’s new book “Tideflats to Tomorrow: The History of Seattle’s SODO.” For readers who have not heard, SODO – meaning “South of the Dome” – is the name for the neighborhood south of King Street, long ago reclaimed from the tidelands, but more recently divested of its Kingdome. All that is recounted in the book and much more.

Reader’s can contact the publisher via fairgreens@seanet.com, or check their neighborhood bookstore – those that have survived.

WEB EXTRAS

Jean is away in Illinois attending a Knox College theatrical performance in which his youngest son, Noel, plays one of the principal parts. When the last performance was completed and the congratulations too, Noel went off with the players for the cast party and dad returned to his room in a converted Ramada Inn on the town’s principal square. There from his lap top he inserted this week’s story of the B-29 crash into this blog and asks me, “Anything to add, Paul?” Yes Jean we’ll put up the map we arranged to help locate the proper spot on which to shoot your “now.” And it also shows the crash site at the northwest corner of the Frye Plant. And we have grabed a low-resolution aerial that shows the damage looking to the southeast. A look at the Frye’s first plant on the same site when it sat of pilings over the as yet unreclaimed tideflats follows. Then up to the Frye Mansion on First Hill, at the s0utheast corner of 9th Avenue and Columbia – one block south of St. James Cathedral. Here we first insert a photograph of the old Coppins Water Tower. From the mid 1880s to about 1901 the big well below that tower was the principal provider of fresh water on First Hill. The Frye mansion took it’s place. Emma and Charles Frye collected genre paintings and . . . well more is told below with the feature that first appeared in The Times in 1997.

(As Ever – Click Images to Enlarge Them – sometimes click twice.)

[Here we hope to insert the “now” that appeared in Pacific in 1997. It is temporarily in a shuffle of negatives – somewhere in this studio.]

THE FRYE’S SALON

(This first appeared in Pacific Magazine, April 6, 1997)

Here’s an aside to the hoopla encircling the reopening in new quarters of the 45 year old First Hill institution, the Fry Art Museum: a short notice of whence came these paintings of cattle, angles, graybeards and bucolic paths.

After returning from Europe in 1914 with more paintings for their swelling collection the Fryes joined a large gallery to the south wall of their big home on the southeast corner of 9th Avenue and Columbia Street. Soon its four walls were filled “salon style” with ornately framed oils crowding one another from the Persian rugs on the floor to the skylights. This view of the gallery’s northwest corner reveals a fair sampling of the type of often sentimental realism the couple preferred in their art.

Charles Frye who made his considerable fortune as the Northwest’s biggest meat-packer, was especially fond of animal subjects including the German master Heinrich Zuegel’s “Cattle in Water”, here the second oil up from the floor in the second row right of the gallery’s West (left) wall. In the contemporary scene Zuegel’s cattle have been returned with the help of real estate maps, aerial photography — the gallery skylights show well from the sky — and a 100 ft tape measure, to within five or six feet of their original place on the north gallery wall.

(Now we identify below some persons as seen in the “now” photo that appeared in Pacific, but again, not yet here. We will insert that photo from 1997 – when we find it . . . again. Temporarily we will include, directly below, the clip from Pacific.)

All this figuring puts the painting in the living room of the St. James Cathedral Convent which replaced the Frye home in 1962, ten years after the Frye collection had been moved one block east to the then new namesake museum. Standing about the painting — and supporting it — are Sisters Anne Herkenrath and Kathleen Gorman, right and center respectively, both distinguished members of the order Sisters of the Holy Names and therefore long-time Seattle educators.

With the sisters is artist and author Helen E. Vogt. The Frye’s great niece was practically raised in the Frye home and lived with them in the early thirties while an arts student at the University of Washington. As part of my “art direction” for the “now” scene I asked Helen Vogt to hold a copy of her most recent book Charlie Frye and His Times. Before the opening of the Seattle Art Museum in 1933 Seattle’s largest art gallery was the Frye’s, and the public was free to visit it. Pacific Readers wishing to know more about Seattle’s early art history should consult Vogt’s biography of Seattle’s one-time cattle king — packed and framed. Those wishing to make a closer inspection of Zuegel’s deft impression of Cattle in Water, and hundreds more paintings from the Frye’s collection should visit the museum at 704 Terry Avenue. The admission is still free.

There was a tremendous little exhibition on this in the back corridor of the Frye a few years ago, where they usually have this or that show pertaining to the history of the museum. Images and things from that show that have stuck with me include a windtunnel model of the plane and shots of the flight crew’s funeral in the then-still-a-Masonic-Temple Egyptian.

My neighbor, an ex-seabee who served in Korea, was a kid during the war and tells me his dad was head of flight test at ‘Boeings,’ as he calls it. He tells me he remembers going to the crash site with his dad, possibly because his dad had to pick him up at school that day.

Mike

I hope they put that show up again. I missed it. Another friend sent me an e-mail about it as well. I think it was about two years ago I started spending most of my time in my basement – writing.

Paul

I remember as a child- I would have been not quite 5-my Dad taking us to see the Frye building. He was a volunteer fireman, but I don’t know if he worked on this fire or not. I can still remember the smell of burning flesh. It is one of my earliest clear memories.

Was the smell from that exposure at the Frye? If so it was more likely the smell of burning pigs. But then perhaps one burning flesh may smell much like another.

I am interested in pictures of the meat packing plant as my Father, Frank Kern was killed at the plant when the airplane crashed into it. I have never seen pictures of the plant before and saw the article in Sundays paper.

Were you ever able to find more pictures ? My great grandfather was working there, but thankfully survived. I remember as a young girl my grandma taking me to the Frye Art Museum and seeing pictures of that fateful day. I have only one picture of my great grandfather.

Angell, when did your great grandfather work at Frye Packing Co.? My brother found a company photo of almost 40 employees. My dad worked there. I am trying to date this photo. I’m guessing it was taken in the late 30’s to early 40’s since the building was destroyed in the 1943 crash (about which I did not know).

Karl, when did your father work at Frye Packing Co.? My brother found a company photo of almost 40 employees. My dad worked there. I am trying to date this photo. I’m guessing it was taken in the late 30’s to early 40’s since the building was destroyed in the 1943 crash (about which I did not know).

I, too, saw the B-29 on that fateful day. I was 13 and in the 7th grade at McGilvra school. It was lunch time and I was out on the playground. The plane was making a slow turn to the left and one engine was trailing smoke. We read about the crash the next day in the paper. I heard later that one of the men killed in the plane had stolen a ride on it.

Just last week the Wall Street Journal reviewed a new book, WHIRLWIND, about the B-29 use in the Pacific theater during WWII.

Jack

In review they might have landed in the lake – or crashed. In which direction – by the compass – was your “left”?

Paul

Paul,

My view from McGilvra School was looking south. The plane had come north and was going west toward downtown in a slow arc to Port. It was over either Madrona or Washington Park.

If they knew they couldn’t make it I think they could have ditched it in Lake Washington. I believe the old floating bridge was in place at this time.

Jack

Yes the bridge was in place. I suspect in the extreme stress of wanting to save the test, the bomber and their lives they kept hope that somehow they could make it back to the field. The last 30 seconds must have been hell especially. Perhaps they did not change direction then because on change they got some power to lift the plane that wanted to stay on target for Boeing Field rather than commit to a crash and death in the green belt along the side of Beacon Hill.

According to various books I have read, all published before the advent of the internet, the XB-29 airplane that crashed into the Frye plant was not on its first flight, nor was it the first XB-29 to fly. The first flight of an XB-29 reportedly took place on Sept.20, 1942 when Eddie Allen took the XB-29 #1 aircraft into the air for a successful maiden flight of this new type.

That particular aircraft became a test airplane for the Boeing Airplane Company, performing a variety test duties,the nature of which I was told bits and pieces about by our Dad, the late Ben J. Werner, who flew primarily as Flight Test Engineer when he was aboard this aircraft. His hand written logbook designates this aircraft both as XB-29 #1 and AF-42-002, and he logged numerous flights aboard this plane, both during and after the war.

Along the way, XB-29 #1 acquired a name, “The Flying Guinea Pig”, which was painted on the nose, complete with a stylized winged guinea pig wearing a wristwatch, the hands of which pointed to maybe 4:30. A photograph, captioned May, 1948, shows the plane in a Boeing scrapyard, bereft of engines, wing, and more, lying flat on her belly and looking forlorn.

The test bomber which crashed, XB-29 #2, was the second XB-29 to take to the air and it first did so on Dec 30, 1942. Near as I can tell with only rudimentary “research”, XB-29 #2 did indeed have a serious engine fire on its first flight, but the crew, again with Eddie Allen at the controls, was able to land successfully, whereupon a standby firetruck extinguished the flaming engine.

Other information suggests that the doomed XB-29 #2 made more than one “successful” flight prior to the disaster, but I can’t say for sure. There were apparently significantly more than two dozen total XB-29 flight hours prior to the crash and mention is made that many of the flights were of short duration. I suppose researching actual Boeing records would be the grail, and boy, would that be incredible to have access to !!

Another tidbit: the third B-29 to fly nearly crashed on it’s initial takeoff. The control cables were routed incorrectly, causing the controls to be “bass-ackwards” Miraculously, the pilot got the plane back on the ground from just a few very shaky feet of altitude. I’ve seen a grainy film record of this scary event.

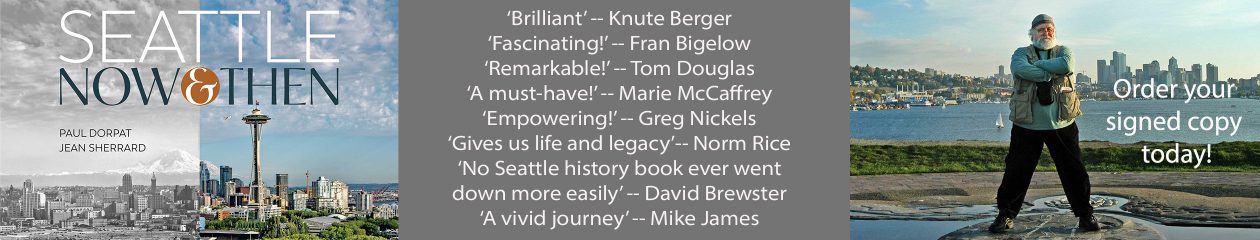

We are lucky to have “Seattle Now & Then to remind us of Seattle’s heritage. It’s my favorite piece in the Seattle Sunday Times. When I read what I thought was a small factual error, I thought I’d chime in, hoping to shed a tiny bit of light.

I goofed with a number. My dad logged in XB-29 #1 as number AF 41-002 in his hand written log not AF 42-002 as I previously posted. He appears to have made 51 flights in this plane but it is late and the print is small.

Some of the tiny boxes in the log book refer to the plane as XB-29 # 1, others as XB-29 #002, and a few as XB-29 #1002.

My thinking is that they are all the Flying Guinea Pig.

My father Harmon was killed in the fry packing plant crash. at noon he would run up stairs to lunch, my mother saw the B-29 burning as it flew north up lake washington. we lived in rainier valley so she had a good view of the plane. thank you all for the stories of an event that changed many lives, sincerely dale b.

i am 34 years old and i am harmon burnisons grandson, i am proud of my grandpa! I have two boys leif and erik. i gave his name to them. i have visited the site. he was a dobro player and a great father. i wish i knew him. a salute to those men! and god bless u all! peace.

Looks like my Uncle and Brother beat me to the page to pay respects.

This story has always amazed me. I wish I had been able to meet my Grandfather. I heard my Grandmother share a million stories about him. She kept it in perspective too. We heard the good and the not so good.

Harmon spoiled his children, he could be moody, he was a wrestler and he was the favorite “kid” in the neighborhood.The children would actualy knock on the door and ask my Grandma if Harmon could come out and play. He loved to read but he always cautioned believe only half of what you read and none of what you hear.

People knew in that day what sacrifice was. When my Grandfather died his wife Marie’s only compensation for his death was a letter in the Seattle Times from Boeing saying that they regretted the loss of life of the crew and the employees in the crash. She did not expect any more. Harmon and Marie had saved money and she used that to get by. When I asked her about how hard it was she looked at me puzzled and questioned me… HARD? I was the one who go to see the sun come up the next morning. During Harmons funeral Marie was taken aside and told that the remains they were to bury were not Harmon’s after all. It had been to difficult to identify the bodies. Marie was 27, with 2 children- ages 8&4 and she was 5 months pregnant with my mother. Her world was unrecognizable but she was grateful to have it.

They truly were the greatest generation. Remarks like my Grandmas were not uncommon. People looked out for one another and there was a sense of unity, I wish we could grasp today.

My cousin; bob maxfield an engineer aboard the X-B29 and was killed. I was in the Coast Guard at the time and was stationed in Seattle in port security, and was told that day to report to the site, as we suspected sabotage which sturned out to be false. I didn’t know until later that my cousin; Bob Maxfield was aboard the airplane. how sad.

My cousin, Barclay John Henshaw, was an engineering graduate from the University of Colorado on that flight. He and his wife, Shirley Jo (Tramill) had lost their infant son Steven to Spinal Meningitis a month prior to the plane accident. In 1944, Shirley Jo married Jack Pyer Williams, a U.S. Air Force pilot who was shot down in Korea eight years later – leaving two daughters. Barclay John was named after my father, John Lawrence Henshaw. In 1944 my family moved from Denver to Delta, Colorado where we became friends of Judge Charles E. Blaine and his wife Mary, parents of another young man lost during that same test flight – Charles E. Blaine, Jr.

Dear Joan,

I saw your post on this website and wanted to share with you that I was researching the fateful crash of the B-29 as I gathered details of the incident for a tribute this Veteran’s Day to my Mom, Shirley, my father, Lt. Col. Jack Pryer Williams, as well as, to Mom’s first husband, John Henshaw. I was so pleased to see your post. I would enjoy being able to communicate with you, if possible. My Mom, Shirley will be 90 yr. old next April and doing well. I have a picture of Mom and John which she gave me. He was a very handsome young man. Mom had two loves of her life and John was the first. In addition to the sacrifices my father and John made, I wanted to honor my mother for the painful sacrifices she made in her life. It is hard to fathom what she endured during those years of her young life. Please feel free to email me Joan. It would be a pleasure to be able to touch base with you. Thank you.

Kris

I was 13 when the plane crashed in Seattle. We were still living in Denver as were most of the Henshaw family. Such a sad day. I am now living in Grand Junction, Colorado but often remember family get togethers. Although John was several years older than I was I remember him so well. Good to hear from all of you, Gladys

When did the Frye plant close and did it change over to Cudahy Bar-s foods. ?

I worked security at Cudahy at the end they closed reopened as Bar-s foods then I worked in the plant till closed permanently March 1984